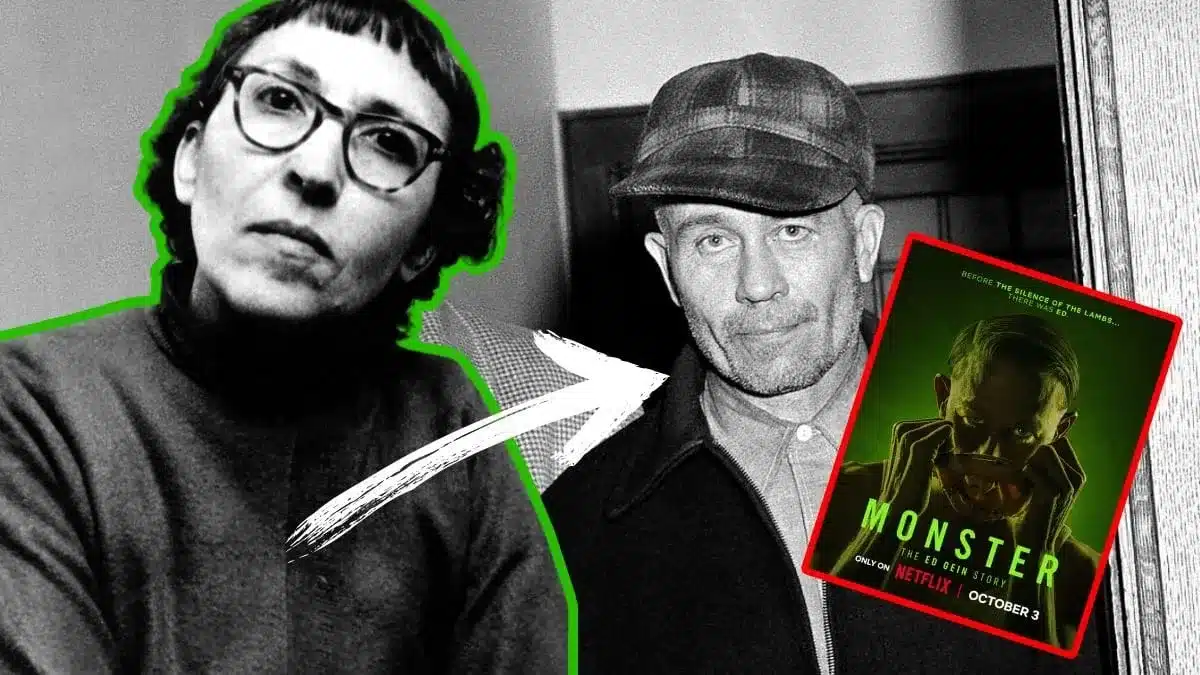

Adeline Watkins’s name resurfaced in 2025 after Netflix’s Monster: The Ed Gein Story dramatized the life of one of America’s most infamous killers. She’s a curious, uncomfortable footnote in a macabre true-crime tale — at once human, contradictory, and much misunderstood. This article untangles what the historical record actually shows about Watkins, explains why her story has been retold, and offers context on how media, memory, and ethics collide in true-crime retellings.

Who was Adeline Watkins?

Adeline Watkins was a Plainfield, Wisconsin resident who briefly became part of the public record after Ed Gein’s arrest in 1957. In the immediate aftermath of Gein’s crimes being exposed, Watkins gave a widely circulated interview in which she said she and Gein had a long personal connection — even describing a courtship and a proposed marriage. That sensationalized claim quickly made headlines and became part of the early narrative surrounding Gein.

The 1957 interview: claim and retraction

What she said

In November 1957, Watkins told a Minneapolis Tribune reporter that she and Gein had a “20-year romance,” that the pair often went to movies together, and that Gein had once proposed. The quotes were colorful and humanizing — words that stood in stark contrast to the horrifying details emerging from Gein’s farm. Media outlets reproduced Watkins’s description and a photo, thrusting her into an unwanted spotlight.

Then she retracted

Within days or weeks (!), Watkins contacted a smaller local paper to correct the record. She said the Tribune story was “exaggerated” and clarified that her contact with Gein was intermittent and far shorter than originally reported. She denied many of the more romanticized details while still describing Gein as “quiet and polite.” The retraction transformed the episode from a tidy human-interest note into a muddled memory — and a cautionary tale about how fast facts can harden into myth.

Why her story matters (beyond curiosity)

Watkins’s episode is more than an odd sidebar for true-crime obsessives. It raises several important issues:

1. How the media shapes reputations

Watkins’s initial, vivid quotes were widely reprinted; the retraction was less splashy. That asymmetry is familiar: sensational quotes travel fast, corrections rarely reach the same audience. historians and journalists point to her case as an example of how early narratives around criminal cases can get locked in even when later evidence complicates them.

2. The ethics of portraying real people in drama

The Netflix series places Watkins center stage, played by actress Suzanna Son. Dramatizations can revivify forgotten figures, but they also carry the risk of blending fiction with fact. When a living or historical person’s reputation is fragile, creative depictions can become the de facto public record — especially when viewers assume a dramatized narrative equates to historical truth.

3. Memory, trauma, and secondary harm

Victims’ families, small communities, and peripheral figures like Watkins sometimes experience renewed scrutiny when cold cases or notorious crimes reenter popular culture. That scrutiny can reopen old wounds or misrepresent lived experience. Good reporting and responsible production practices help reduce that secondary harm.

Separating fact from fiction

Here’s a compact primer on what is (and is not) supported by historical record:

- Supported: Watkins gave a 1957 interview in which she claimed familiarity and even a courtship with Ed Gein. She later publicly retracted most of the romanticized elements and downplayed the intimacy of their relationship.

- Unproven: A sustained, two-decade romantic relationship between Watkins and Gein. The contemporaneous evidence (Watkins’s later clarification, lack of corroborating records) undermines that claim.

- Dramatic license: Contemporary portrayals may amplify or compress interactions for storytelling clarity — always check primary sources when possible.

How producers and journalists should approach this kind of story

When a real person’s testimony is inconsistent, good practice includes:

- Seeking primary documents (original interview transcripts, local newspaper archives) rather than relying on syndication or later retellings.

- Noting retractions prominently. If a historical subject recants or clarifies, that correction deserves the same exposure as the initial claim.

- Being transparent in dramatizations — a short on-screen note like “some events have been fictionalized” helps viewers separate fact from invention.

These are not just niceties; they are practical safeguards against misrepresentation and legal risks (e.g., defamation claims when living people are depicted inaccurately).

What the Watkins episode tells us about Ed Gein’s case

Watkins’s fleeting celebrity highlights the broader social hunger for human details when monstrosity is discovered. The public, understandably, wants to understand how a neighbor could live beside a person who committed such crimes. Yet the Watkins story also demonstrates how human complexity resists tidy explanation: acquaintances may have been kind, deceptive, or confused — and witnesses are fallible. The reliable documentary record (police files, medical reports, and well-sourced journalism) remains the best basis for understanding the past.

Conclusion

Adeline Watkins is not a villain, nor is she a central actor in Ed Gein’s crimes. She is a human figure who briefly became part of a sensational story — an example of how media, memory, and dramatic retelling can warp what actually happened. The responsibly curious reader should value primary sources, heed retractions, and be cautious about assuming dramatized portrayals reflect historical certainty. After all, the most ethical form of storytelling honors both truth and the dignity of real people.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Was Adeline Watkins Ed Gein’s girlfriend for 20 years?

No. Watkins initially claimed a long courtship in a 1957 interview, but she later retracted those claims and said their contact was far more limited. Contemporary records support the retraction.

Q2: Is the Netflix portrayal historically accurate?

Dramas take creative license. Netflix’s Monster uses Watkins as a narrative device; viewers should consult historical sources (archived interviews and news reports) to separate dramatization from documentation.

Q3: Why did Watkins retract her statements?

Historical reporting suggests she felt the initial coverage had been exaggerated and that publicity made her uncomfortable. She told a later local paper that the Tribune story “was blown up out of proportion.”

Q4: Did Watkins visit Gein’s home or know about his crimes?

Watkins denied ever having been inside Gein’s house. There is no evidence she knew about Gein’s criminal activities before they were exposed.

Q5: What lessons do journalists and producers take from this episode?

Highlight corrections as prominently as sensational originals, verify claims with primary sources, and be transparent when dramatizing to avoid turning fiction into assumed fact.